Born into Brujeria: A Mayan Sorcerer’s Experience in a Transgressive Tradition

First-Hand Knowledge of the Hidden World of Guatemalan Folk Magic and Its Evolution from Secrecy to Modern Practice

Understanding Brujeria

Brujeria is more than just witchcraft; it is an essential part of the Latin American spiritual mosaic. Brujería is a syncretic Latin American tradition that combines Indigenous religious and other magical practices under the overhang of Catholicism. Today, I will focus on Guatemala, where ancient Mayan magic intersects with Catholic and African spirituality, brought together through syncretism. This blend has allowed old Mayan spirits to be cloaked as Catholic saints—a testament to the tradition’s deep historical roots and adaptability.

The term “brujeria” itself carries complex connotations. Practitioners are called Brujas (feminine) or Brujos (masculine sometimes even gender neutral). While the Catholic Church had deemed them as evil and demonized them, practitioners have maintained their traditions despite centuries of persecution. This resilience speaks to the profound cultural importance of these practices within indigenous and mestizo communities.

*spiritual based gathering in Chichicastenango, Guatemala

The Evolution of Language and Tradition

A quick note on terminology: in contemporary discourse, there is a nuanced distinction between ‘Maya’ and ‘Mayan’. Academically, ‘Mayan’ refers to languages and the calendar, while ‘Maya’ encompasses other cultural elements. Nevertheless, you will hear both used interchangeably as descriptors of the magic ingrained in the Maya civilization.

* Maya woman and child Lake Atitlan, Guatemala

The K’iche’ people represent one of the largest Maya groups in Guatemala. Estimates place the current K’iche’ population of Guatemala at around 2 million. This language and traditions have survived despite centuries of colonization and, more recently, the devastating civil war that particularly targeted indigenous communities. According to the Guatemalan Historical Clarification Commission, Maya people in Southern Él Quiché were 98.4% of total victims.

Historical Context and Syncretism

The syncretic nature of Brujeria emerged from a complex historical process. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Maya people in the northern Yucatán Peninsula, especially around the region of Izamal, experienced a process of conversion to Christian Catholicism led by a limited number of Spanish friars and priests. However, rather than complete conversion, what emerged was a fascinating blend of traditions.

Despite violent Spanish subjugation beginning in 1524, many of those traditions still survive. Coerced conversion had mixed results, as the Maya in certain territories often did not replace or abolish their beliefs in favor of Christianity, but rather added this new faith as another layer. This layering process created the unique spiritual landscape we see today in Guatemala, where syncretism, combining Maya religious beliefs and Catholicism, is a major player in highland Maya spirituality.

Spirits and Syncretism in Brujeria

Brujeria is a tapestry of spiritual practices aimed at practicality—healing, protection and beyond. The spirits involved represent both ancient deities and syncretic saints, revered for their powers and roles within the community. These figures symbolize the deep blend of tradition and convergence of cultures fundamental to Brujeria.

*Candle arsenal, Botanica Dayana’s, Hyattsville, MD

San Simón/Maximón

One of the most prominent figures in Guatemalan folk spirituality is Maximón, also known as San Simón. Maximón is a Maya deity and folk saint, represented in various forms by the Maya peoples of several towns in the Guatemalan Highlands. His worship represents a perfect example of religious syncretism, as the modern character of Maximón is thought by analysts to be a blend of several historical, biblical and Maya mythological figures. These include Pedro de Alvarado, Judas Iscariot, Saint Peter and Rilaj Mam.

*Brotherhood of Maximon, Guatemalan Highlands

Maximón’s appearance varies greatly by location. While he is popularly depicted as a man in a suit and hat, this is not a constant. In Santiago Atitlán, he wears colorful garlands and scarves, while in Zunil, he wears sunglasses and a bandana. This variability reflects the localized nature of folk traditions and how different communities have adapted the figure to their specific needs and contexts.

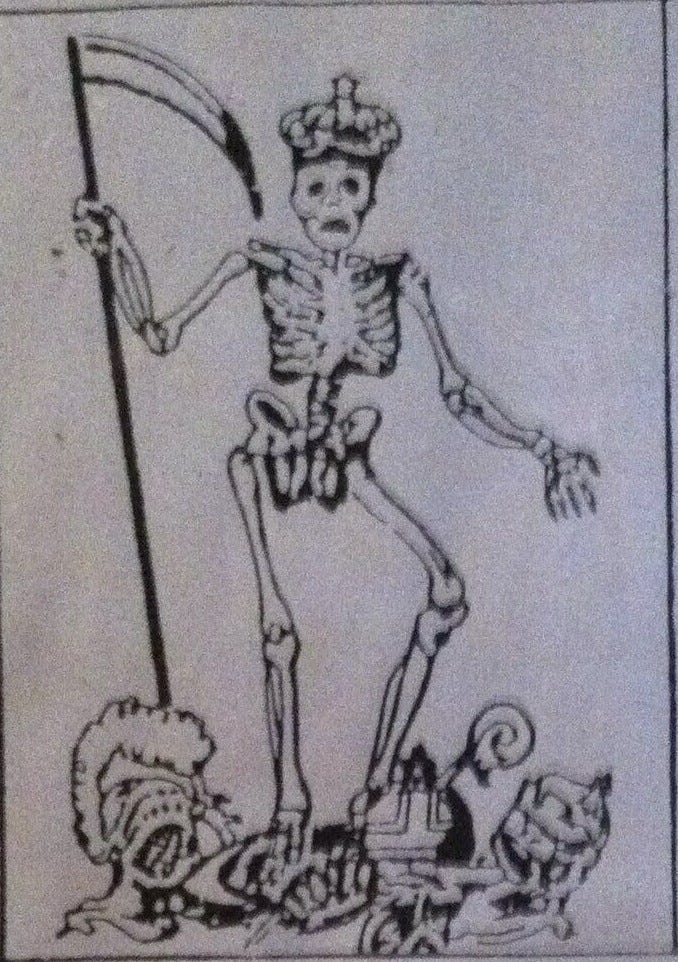

San Pascual Rey

Another significant figure in Guatemalan Brujeria is San Pascual Rey (Rey Pascual), a skeletal saint with deep roots in both Maya and Catholic traditions. San Pascualito (also known as San Pascualito Muerte and El Rey San Pascual) is a folk saint associated with Saint Paschal Baylon and venerated in Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. He is called “King of the Graveyard” and predates the popular Santa Muerte by over 160 years, making him the oldest known identifiable robbed skeletal spirit of the Americas.

The origin story of San Pascual Rey provides fascinating insight into the syncretic process. According to historian Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, it is said to have appeared in 1650 in a vision of an indigenous Guatemalan man in San Antonio Aguacaliente (modern day Ciudad Vieja). The man was dying from an epidemic fever called cucumatz in Kaqchikel, and had received the last rites before a tall skeleton in glowing robes appeared to him.

*Classic depcition of San Pascual Rey

The skeletal apparition who appeared to the Kaqchikel elder was a textbook case syncretism — the fusion of discrete religious elements — a Catholic saint, the European Grim Reaper and Mayan death deities which resulted in a new vernacular holy figure, Rey Pascual. Today, devotees leave thank you notes, offer capes or burn candles. The color of the candle burned signifies the nature of the request for intercession: red for love, pink for health, yellow for protection, green for business, blue for work, light blue for money, purple for help against vices, white for the protection of children and black for revenge.

Community and Solitude in Rituals

In Guatemala, Brujeria is practiced both communally and in isolation, depending on the region. Urban areas, like where my mother was raised, often see solitary practices, a reflection of the ever-watchful eye of Catholic doctrine. This dichotomy reflects the complex relationship between indigenous spirituality and institutional Christianity.

*Inglesia De San Tomas Church

In rural areas, however, magic continues to reaffirm social bonds and resolve community grievances. Nowadays, a ‘Daykeeper’, or divinatory priest, may stand in front of a fire, and pray in Maya to entities such as the 260 days; the cardinal directions; the ancestors of those present; important Mayan towns and archaeological sites; lakes, caves or volcanoes; and the creative forces named in the Popol Vuh.

The Role of Ajq’ijab’ (Spiritual Leaders)

The Ajq’ijab’ (plural of Ajq’ij) are the traditional spiritual leaders and Daykeepers of the Maya people in Guatemala. The conclusion of the Civil War provided the conditions that motivated the spiritual leaders (Ajq’ijab’) to leave secrecy in the 1990s. This emergence from secrecy coincided with the peace process in Guatemala and represents a significant shift in Maya spiritual practice.

K’iche’ Daykeepers use puns to help remember and inform the meanings of the days. Divinatory techniques include the throwing and counting of seeds, crystals and beans, and in the past also – apart from the count – gazing in a magical mirror (scrying), and reading the signs given by birds (auguries). These practices connect contemporary practitioners with ancient Maya traditions while adapting to modern contexts.

The Sacred Geography of Brujeria

Sacred sites play a crucial role in Guatemalan Brujeria. Modern-day Maya religious practices, also known as costumbre, often take place in caves, archaeological sites and volcanic summits. They often include offerings of candles, flowers and liquor with the sacrifice of a chicken or other small animal thrown in for good measure. These locations are not chosen arbitrarily but represent portals between the physical and spiritual worlds.

The chapel dedicated to Rey Pascual in Olintepeque exemplifies how folk spirituality has created its own sacred spaces. Since the folk saint is not recognized by the Catholic church, the villagers in Olintepeque decided to construct an exclusive chapel dedicated to him. This represents the community’s assertion of their spiritual autonomy and the importance of these folk traditions.

The Pursuit of Fulfillment in Brujeria

Brujeria is powerful, yet practitioners must navigate the delicate balance of aggression and consequence. Metaphysics operates on principles of reciprocity and balance, reflecting Maya cosmological concepts. The mantic calendar has proven to be particularly resistant to the onslaughts of time. This 260-day sacred calendar continues to guide ritual practice and divination.

It is crucial for enthusiasts, especially those outside traditional contexts, to manage their expectations and realize that magic is not a foolproof pathway to altering reality despite the rumors and stories one may hear about the functional formulas of cultural practices such as Brujeria or Palo Mayombé. The tradition demands respect, understanding and an appreciation for its cosmological underpinnings. As modern practitioners like J. Allen Cross emphasize, cultural sensitivity and proper education are essential for those approaching these traditions from outside their original context.

Modern Challenges and Adaptations

The tradition of Brujeria faces multiple challenges in the contemporary world. With the increasing rate of persecution amongst practitioners since the colonization of the Afro-Latino Caribbean, Brujería has been forced into modernization to combat erasure. This modernization process involves both preserving traditional knowledge and adapting to new contexts.

Educational barriers continue to affect the transmission of traditional knowledge. The impact of evangelical Christianity has also created new tensions. According to some estimates, a third of Guatemala now claims adherence to Protestantism and, more specifically, Evangelical Christianity—a violent form of Christianity in Guatemala. This religious shift has created new pressures on traditional practices, though many practitioners maintain dual religious identities.

The Diaspora and Transnational Brujeria

As Guatemalans have migrated internationally, so too have their spiritual practices. As many Guatemalans have migrated to areas such as Mexico, the United States and Canada, the veneration of Maximón has traveled beyond the borders of Guatemala, where he is more commonly known as San Simón. This diaspora has created new contexts for practice and new challenges for maintaining authenticity.

Contemporary authors documenting these traditions note the existence of altars to folk saints in major U.S. cities. This transnational dimension of Brujeria represents both an opportunity for preservation and a challenge for maintaining cultural integrity as practices adapt to new environments and interact with other spiritual traditions.

Addressing Brujeria’s Challenges

What makes Brujeria particularly fascinating is its nature as a living, evolving tradition. The collective discussion about the great crises of the 20th century - land dispossession, work on coastal plantations, religious conversion, the power of ancestors, community identity, migration and political violence - occurred through orality. This oral tradition continues to be the primary means of transmitting knowledge, even as books and digital media provide new platforms for sharing information. The tension between preservation and innovation, between secrecy and public practice, continues to shape how Brujeria evolves in the 21st century.

The tradition of Brujeria faces challenges—primarily a lack of integration into the broader cosmologies and a tendency towards practical, transactional magic. This is often a result of historical repression and educational barriers. The systematic targeting of indigenous peoples during Guatemala’s civil war created ruptures in traditional knowledge transmission that communities are still working to heal in addition to the ruptures occurring since the advent of colonialism.

Nevertheless, the field can broaden and improve by fostering deeper cosmological awareness and encouraging educational growth. The 1990s were a decade of cultural and political change in Guatemala. Negotiations led to a Peace Agreement between guerrilla forces and the Guatemalan government after a 36-year Civil War. Mayan ceremonies, based in cosmology, mystical beings, the Popol Wuh book, the 260-day calendar and the burning of natural materials, emerged in public spaces for the first time in hundreds of years.

This begs the questions:

as more historical evidence of pre-columbian ritual is discovered and native practitioners become more educated, what is the point of holding on to syncretism?

in a world where freedom of religion is allowed, why hold onto folk saints when we know their pre-columbian identities?

why hold on to catholic proxies that double as a form of subversion yes, but also things that keep you in a catholic loop?

Conclusion from my Experience

Brujeria is not merely a collection of spells. The ways in which the Yucatec Maya adapted and integrated elements of Catholicism into their existing spiritual beliefs, demonstrate the resilience and adaptability of their culture, in the face of significant external challenges. This resilience continues to characterize the tradition today.

For those of you interested in embracing or studying Brujeria, remember that its true potential resides in both honoring its rich traditions and encouraging a broader understanding of its place in a larger universe. The practice requires not just technical knowledge but cultural sensitivity, respect for its origins and an understanding of the historical and contemporary struggles of the communities that maintain these traditions.

This also means understanding the limitations of Brujeria. As I said before, without a holistic cosmology Brujeria and spellwork is not living up to its full potential. But being aware of the educational barriers should signal that some of these “traditions” may not be as old as mentors make them out to be. Brujeria is due for an evolutionary step forward and that does not mean by simply adding more things. New research and comparative analysis between practitioners offer more than enough authentic expansion without having to appropriate trends from other forms of magic, which oftentimes gets mistaken for innovation.

Services

Cosmic Axis Reading: a transformative three-part divination experience rooted in Maya cosmology that helps you find your center and align with your true purpose through a sacred seven-card spread representing the five cardinal directions.

Mayan Pyramid Path Reading: a comprehensive divination service using a sacred 13-card pyramid spread based on Maya numerology to reveal your life’s natural energetic rhythm and help you navigate major transitions with clarity and courage.

Mayan Astrology Birth Chart Reading: an in-depth soul blueprint analysis that reveals your cosmic destiny through ancient Maya Telluric Astrology, analyzing your daysign, trecena, Venus cycle, Lord of Night, birth year energy and peak manifestation days based on your exact birth moment.

Love that this posted at 444. Great piece!!