American Archons

The Gnostic Experience of Mesoamerican Colonization

May 3rd is known as the “Day of the Mayan Cross” in Belize. No, it is not the Christian cross as one might assume at first glance. No, the Mayan Cross did not come from Jerusalem. This green cross came from Xocen Cah. No, this cross is not called a crucifix. This green cross is called the Ki’ichkelem Yuum. No, this cross cannot be found at Golgotha. This green cross can be found etched into the sarcophagus of Kinich Janaab Pakal the Great. This green cross is the model of our sacred Yaxché(Ceiba Tree)—the cosmological superstructure or Axis Mundi.

Despite the pre-columbian origins of our cross, colonial entities have tried to revise our history and malform the light of creation. Is that not what a certain “Black Iron Prison” does?

The Gnostic myths of antiquity and the historical colonization of Mesoamerican peoples reveal striking parallels in their narrative structures, symbolic frameworks, and material consequences. Though separated by time and context, both stories unveil similar patterns of cosmic and earthly power struggles.

*photo credits to Nohoch Máak Chuc

Narrative & Symbolic Parallels

False Gods and Usurped Authority

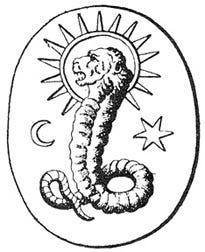

Both Gnostic mythology and the Mesoamerican colonization narrative center on catastrophic intervention by foreign powers. In Gnostic texts, the true divine realm (Pleroma) is separated from our flawed material world, which was created by the Demiurge—a lesser deity born of cosmic error who falsely believes himself to be the supreme god. This Demiurge and his archons rule the material world, trapping divine sparks (human souls) in ignorance.

Similarly, the Spanish conquest narrative involves foreign powers arriving from across the sea, imposing their cosmological understanding as the only truth while dismissing indigenous knowledge systems. The conquistadors, like the Demiurge, claimed to represent the true god while establishing systems that trapped indigenous peoples in new political, economic, and spiritual hierarchies.

Multiple Maya groups would label the conquistadors Kaxlan, more than likely a contortion of Castilian Spanish. In the Books of Chilam Balam and Maya folk-culture, the Kaxlan undergo an expansion and are spiritual entities of the conquest. I would argue that there is nothing more gnostic than metal-clad alien invaders forcing a population to hate themselves and love the idea of a homogenous sovereign. Double the gnostic seasoning with the Kaxlan as an enforcing spirit armada.

The Gnostic Demiurge proclaims, "I am God and there is no other God beside me," despite being merely a lesser, flawed creation compared to the greater numinous. This mirrors how Spanish colonizers positioned themselves as representatives of the one true God, declaring indigenous deities as false or demonic while establishing themselves as new authorities.

Divine Sparks and Cultural Resistance

In Gnostic thought, divine sparks (human souls) remain trapped in material bodies but can be awakened through gnosis (spiritual knowledge). Despite colonial oppression, Maya cultural knowledge, languages, and traditions persisted—sometimes hidden, sometimes syncretized with Christian elements—preserving sparks of pre-colonial identity despite attempted erasure.

This idea of sacred substance is echoed in Mesoamerican creation stories. Previous attempts to create humans resulted in mankind assembled from mud and wood. Both prototypes were regarded as soulless and hollow beings. It was only when the Yuumtsilo’ob—the Maya equivalent of deities, mixed their blood with the promising substance of Ixim(corn) did they create the humans that would give rise to civilization.

Archons and Colonial Hierarchies

The Demiurge's archons (ruling powers) or in this case, Kaxlan, maintain cosmic ignorance and control. Similarly, colonial systems established hierarchical structures—encomiendas, religious missions, racial castes—that maintained indigenous peoples in positions of subjugation and enforced ignorance of their own traditions.

Physical Violence & Imprisonment

Gnostics viewed the material body as a prison for the divine spark. The colonial system physically imprisoned indigenous peoples through forced labor systems, reducciones (resettlement policies), and restricted movement.

A key difference between Gnosticism and indigenous philosophy is that the Maya do not forsake the physical body. Flesh and the natural world are meant to be respected and tended to.

Both systems involve the violent suppression of knowledge. The Demiurge keeps souls ignorant of their divine origin, while Kaxlan colonizers systematically destroyed Maya codices, monuments, heirlooms and other knowledge-recording devices, replacing them with European epistemic frameworks.

Transformative Resistance

Despite these parallels of oppression, both narratives contain seeds of resistance. Gnostic traditions offered paths to awakening through hidden knowledge, while indigenous resistance took many forms—from open rebellion to subtle preservation of cultural practices, language, and cosmological understanding. In 2025, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 is being unlawfully used to target the descendants of Mesoamerica that live in the modern United States. Contending with principalities of “orange” ignorance is now a part of the Meso-gnostic canon.

The resonances between Gnostic mythology and Mesoamerican colonization reveal a timeless pattern of power, knowledge, and resistance. In both narratives, dominant powers attempt to remake reality according to their vision while suppressing alternative understandings. Yet in both, sparks of alternative knowledge persist, offering pathways to liberation from imposed systems of control. These parallels invite us to recognize colonization not merely as a historical process but as a cosmological event that restructured reality itself for the colonized peoples. The relation is clear: spirituality is resistance!